The “miracle” trains and the carbon-free, smoke-free journey from Milan to the Lakes

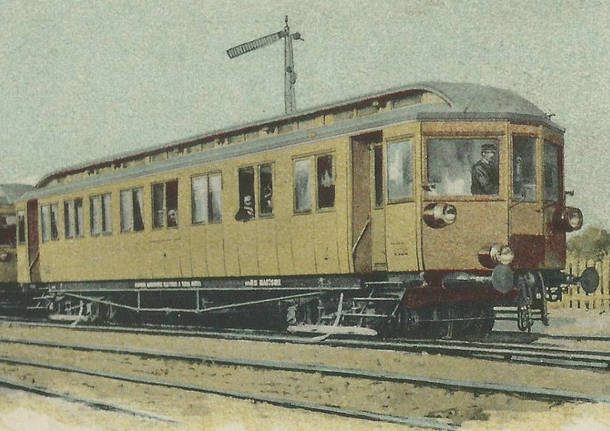

When Italy’s first electric trains made their debut in 1901, they were intended for tourism to Lake Lugano and the Verbano area. The “Varesine” trains adopted the electrified third rail system, which was innovative but dangerous, which lasted exactly half a century, until 24 March 1951.

In the early 20th century, to the eyes of a wealthy inhabitant of Milan, or to those of a shepherd boy from Arcisate, these trains must have seemed an almost unbelievable marvel. There was no smoke and no steam: the carriages were moved by an invisible force, electricity.

These were the “Varesine”, the very first electric trains in Italy: the energy that moved them came from a third rail, next to the two that guided the wheels, a third rail that carried a 650 V current. This was a very modern system at the time, but it certainly had its dangers, and for this reason it was eventually eliminated: this system lasted half a century, until it was completely deactivated on 24 March 1951, exactly seventy years ago.

At the dawn of electricity, it was not clear how to apply the power of the “clean coal” to trains; was it better to bring the electricity on board the wagons or to create a power line from which the locomotive would get the current needed to move the train? At first, it was decided (or rather, a state commission decided) to experiment with both systems on the two main networks that ran Italy’s railways, the Mediterranean Network and the Adriatic Network.

The battery trains (or accumulator trains) were tried out on the Milan-Monza railway and on a short stretch near Bologna, and those that took the electricity from a line running parallel to the track were tried out on the Milan-Varese-Porto Ceresio line. Commemorative postcards (such as the one from which the first photo above is taken) referred to them as “treni a terza rotaja” (“third-rail trains”).

Varese station, in 1905, with the very new “third-rail” electric trains. Photo taken from the website photorail.it.

Electricity was a source of pride for the railways, and what better publicity than its use on the most prestigious lines?

This is why the line to Varese and Lake Lugano was chosen: this was a holiday area for the people of Milan (especially the middle classes), who were already building houses on the green hills overlooking the blue lakes. And there was another advantage: to get to Varese, you had to pass through Upper Milan Province, the area of Legnano, Busto Arsizio and Gallarate, one of the few areas where there was industry, with the need to move raw materials for the factories and products to be sent to the cities. There were also skilled workers and technicians, who often went back and forth between factories.

The electricity came from a power station in Tornavento, near Lonate Pozzolo, but later, the line was connected to the hydroelectric power station in Varzo, in Ossola Province, almost 150 km from Milan. The high-voltage current arrived and was converted to 650 Volts, in special ‘transformer substations’ along the line, which, in some cases, can still be seen.

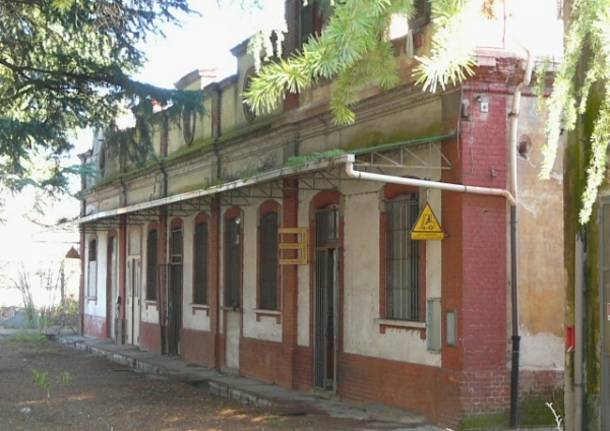

The ruins of the “substation” in Gallarate, in Viale dei Tigli. Electrification also created a new working aristocracy of skilled workers, who were employed on the systems

The “Varesine” trains, and tourism of the belle époque

The Touring Club’s first Red Guide, which was published in 1914, already recommended travelling to Varese on the Porto Ceresio railway, which, in 1905, had been taken over by the Ferrovia dello Stato (FS – State Railway company). The line was intended to be “chosen by the Ferrovia Nord railway company, because the equipment (trains etc.) was more comfortable and faster”, thanks to electrical power.

Gone was the smoking steam locomotive that blew ash and soot onto the spotless dresses of the Milanese ladies; the people went to Central Station, outside the gate of Porta Venezia (now Piazza Repubblica) and looked for the platform for Varese, without getting too close to the panting black locomotives. And the number of journeys from Milan to the foothills of Varese (twenty trains a day, and more!) made the ride comfortable even for short stays.

The railway bridge, which existed until 1931, between Via Galilei and Via Fabio Filzi, in Milan, while a tram is passing (with the church of San Gioachimo in the background). The large sign publicises the modern electric trains; curiously, Gallarate, and not Varese, is mentioned as the branch line station.

Country houses also multiplied along the railway, making the fortune of villages that had already been holiday resorts for centuries. In Gazzada, for example, the rich 16th-century Villa Cagnola was joined by the neo-Gothic Villa De Strens, which was completed (as chance would have it) a few years after the introduction of the electric trains, which shortened the journey from Milan. In Valceresio, new, middle-class villas were added to the noble villas of Porro Pirelli, in Induno, and Cicogna Mozzoni, in Bisuschio.

Even the heads of families could afford to commute between the city and the Varese mountains. Within a few years (from 1906), holidaymakers could even get as far as the small world of Valganna, with the electric train and its white carriages, which waited for a connection in Varese before continuing on to Luino and Ponte Tresa. But the new neo-Gothic and neo-Romanesque houses, with their turrets, also proliferated in the then very green Valdarno, in Castronno and Albizzate; in addition to the images of the stations, these also appeared on the postcards of these villages, as symbols of modernity and good taste.

“Clean coal” and modernity, from Milan to Naples

The 650 Volt, third-rail system had proved to work so well that the FS decided to use it in other parts of Italy, in another miraculous project, the Naples metropolitan railway, the first to open in Italy, in 1925, with four underground stations in the centre of the city.

The FS then introduced new locomotives capable of exceeding 100 km/h and also locomotives that also pulled international trains between Milan and Gallarate, which then continued by steam locomotive to the Simplon Pass. In 1905, the main train maintenance yard was also installed in Gallarate, which in turn contributed to the area’s industry, as it employed hundreds of skilled workers.

The E321 engine carriage was used on the Varese lines and on the Naples underground lines. The engine carriage in the photo is in the Science and Technology Museum, in Milan.

A few years later, in 1931, Milan’s new Central Station was inaugurated. The old one was demolished and only a secondary wing of the building remained, serving only the trains to Varese; the station was named Milano Porta Nuova, although everyone took to calling it more informally by what it was, the “Varese train station”.

The station of Milano Porta Nuova, in the 1950s. Next to the advertisement for Chlorodont toothpaste, there is the sign in large print “Linee Varesine”.

“If you touch it, you will die”: a system that did not pollute, but was dangerous

Meanwhile, in Italy, other forms of railway electrification had also begun to be tried out, based no longer on a line on the ground, but on an overhead line, where the cable was above the trains, as they are today; this system was ultimately preferred. In the 1930s, newspapers wrote that, “For safety reasons, use of the third rail had to be limited to low voltages and could not have extended applications.”

“If you touch the top rail, you will die”; these signs were accompanied by skulls that warned of the danger. Isolated from the ground on special porcelain supports, the third rail became deadly if touched; in the stations, it was shielded with wood, but there were many tragedies. We can find traces of this in the pages of newspapers: “Soldier dies of a violent electric shock in Gallarate”, for instance, was the headline of La Stampa, on 4 February 1941, recounting the unfortunate carelessness of Guido Zambon, who (“on his way from Trieste, heading for Sesto Calende” and “obviously unaware of the danger of the third rail”) touched the steel carrying the 650 Volt electricity.

The reconstructed third rail at the National Railway Museum in Pietrarsa, near Naples

After the Second World War, it was decided to electrify also the Milan-Domodossola line (1947), but this time with a more modern 3000 Volt system, which is still in use today.

The two systems coexisted for no less than four years, as far as Gallarate, before the conversion to the new system was completed on the line to Varese and Porto Ceresio: the dangerous third rail was deactivated on 24 March 1951.

In those years, it was the maintenance yards in Via Pacinotti, Gallarate, that were responsible for the hard work of transforming the trains from the old to the new system, a job of which the veterans among the Gallarate workers were proud, because it was all carried out “in house”, and it was very complex.

The “adjustment department” of the Maintenance Yard in Gallarate: this is one of the parts that dates back to the beginning, in 1905. The yard closed in 1997, and today, it is in a state of abandoned (the photo is from 2010).

Le Varesine: a name that is coming back

The locomotives rebuilt in the 1950s changed their numbering (the train’s “number plate”,) but their nickname remained: for thirty years, they operated around Milan, on the lines in the area, primarily to Novara, Piacenza and Lomellina, but they always remained “Le Varesine”. Now, the FS Foundation (which is responsible for protecting the historical heritage of the FS) is restoring them to run as vintage trains.

The interior of the restored E623 engine carriage

However, there is another use of the name that brings us to the present: it is the “Varesine station” in Milan, which survived for thirty years, from 1931 to 1961, when the tracks were brought to an end in the Porta Garibaldi area, with the opening of the station that thousands of Milanese commuters use today. The space occupied by the old station was neglected, and for decades was home to an amusement park that everyone knew as “Le Varesine”.

Is this the end of the story? Nearly: because then the name (in its final guise) was acquired by the real estate company which handled the construction work in the area in the 2000s. Today, there are skyscrapers and maybe the term “Varesine” is coming to the end of the line, really.

Sources and bibliography:

Alessandro Albè, Le “Varesine”. L’avventura della terza rotaia in Italia dal 1900 al 1950. Le esperienze estere (The Adventure of the third rail in Italy, from 1900 to 1950. The experience abroad), Turin, Elledi, 1986.

Giovanni Cornolò, Automotrici elettriche dalle origini al 1983 (Electric railcars from their origin to 1983), Duegi Editrice, 2011.

Websites: photorail.it and stagniweb.it

La Stampa: online archive.

Translated by Bignoli Mariachiara, Aldea George Andrei and Villa Michela

Reviewed by Prof. Rolf Cook

La community di VareseNews

Loro ne fanno già parte

Ultimi commenti

lenny54 su Pomeriggio di botte in piazza Repubblica a Varese: rissa tra una ventina di ragazzi, coinvolti anche minorenni

elenera su Un progetto che unisce sostenibilità e formazione: aiutaci a realizzare "La Via delle Api"

Felice su Stretta sul reddito di cittadinanza, la Finanza di Varese denuncia 29 persone fra imprenditori e giocatori on line

Felice su Preoccupazione alla Mv Agusta: le difficoltà di Ktm fanno tremare i lavoratori della Schiranna

Felice su Varese si ferma per lo sciopero generale: corteo di oltre 3 mila persone in centro

PaoloFilterfree su Più di mille vittime negli anni di piombo ma Busto Arsizio sceglie di ricordare solo Sergio Ramelli

Accedi o registrati per commentare questo articolo.

L'email è richiesta ma non verrà mostrata ai visitatori. Il contenuto di questo commento esprime il pensiero dell'autore e non rappresenta la linea editoriale di VareseNews.it, che rimane autonoma e indipendente. I messaggi inclusi nei commenti non sono testi giornalistici, ma post inviati dai singoli lettori che possono essere automaticamente pubblicati senza filtro preventivo. I commenti che includano uno o più link a siti esterni verranno rimossi in automatico dal sistema.